UNDERVALUED CORONAVIRUS HEROES

While nations were under lockdown during the depth of the pandemic, millions of people around the world worked remotely from home. At the same time, there was an even bigger cohort of essential workers for whom it was business-as-usual as the coronavirus swept the land.

These unlikely heroes drove the trucks which delivered our goods, stocked the supermarket shelves which provided our groceries and prepared the takeaway meals which kept us fed. Other essential workers – like farmhands, meatpackers, store cashiers and warehouse clerks – also helped keep the economy’s lights on.

When the pandemic hit, jobs previously labelled “low skill” were reclassified as “essential”. As cities enforced quarantines and shoppers squabbled over the last roll of toilet paper on the supermarket shelf, “essential” employees were out and about keeping societies functioning. Their efforts largely went unnoticed even though they were everywhere.

Doctors, nurses and other health professionals bore the brunt of the outbreak and were the most at-risk population. They received an outpouring of gratitude from citizens and governments for their tireless patient care. Non-medical frontline workers, however, were less recognised. Nonetheless, this other layer of critical workers continued to show up on-the-job to help maintain a semblance of normality for others.

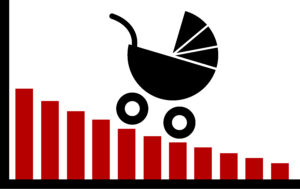

The pandemic has shone a light on the stark workplace divide between people who can work from home and those who can’t. Lower paid workers – like factory employees, security guards and supermarket staff – don’t have the option of working remotely. In contrast, highly compensated workers – like managers and other professionals – are able to shelter at home.

Alison Pennington, a senior economist at The Australia Institute’s Centre for Future Work, told ABC News that it was easy to see how the pandemic work regime could compound inequality in Australia.

We estimate people who can work from home are earning around 24 per cent more than those who can’t. They’re also more likely to have paid sick leave benefits — while essential workers who are turning out every day, are more likely to work for lower pay, but also less likely to have sick leave.

Pennington said those differences were creating greater inequality, not only in incomes, but also health outcomes as essential workers faced the higher risk of infection without the income safety net of sick leave. She stated:

… coming through this regime, what we’re going to find is that the pandemic is going to require a universal entitlement to sick leave if we’re going to be able to work through the virus and keep everyone safe.

The Centre for Future Work estimates that only around 15 per cent of Australian workers currently have the option of working remotely full-time. That figure is expected to double as companies quickly adapt to allow more of their employees to stay away from the office. By way of comparison, about a quarter of US workers can easily do their jobs from home.

COVID-19 has revealed how deeply our fates are tied together. It’s not a case of us and them – all workers are in this together. Amid stay-at-home orders, office workers ditched their daily commute while essential workers continued to drive our buses, clean our workplaces, collect our rubbish, cook our food and staff our nursing homes.

Essential workers are just that – essential. They keep communities running, so staying home isn’t an option for them. Risking their wellbeing for the greater good, their sacrifice is a moral calling for all of us. The pandemic added another layer of burden and responsibility to their jobs as they braved the frontlines against an invisible enemy. We owe them our heartfelt thanks.

Thank you to supermarket employees. Often working at minimum wages, they had to deal with epidemic levels of abuse from irate customers. Retail workers are our neighbours and fellow citizens and maybe even the children of your friends. They put themselves in harm’s way to ensure we had access to essential goods – they deserve our highest praise.

Thank you to delivery drivers. While many of us were safely hunkered down at home in isolation, we asked others to drop parcels to our front door. Fulfilling our online orders required the coordinated efforts of workers in warehouses, sorting hubs and courier companies. They provided an indispensable lifeline to the outside world. We are in their debt and salute their wonderful service.

Thank you to transit workers. Buses and trains underpin urban life and during the pandemic they performed the critical task of shuttling workers to and from their jobs. This put transit workers in daily physical contact with members of the public in the confines of a bus or train making social distancing difficult. Three cheers to these quiet achievers for keeping our cities running.

In the war against the novel coronavirus, these and myriad other essential workers were the life support for communities. Yet their work is chronically underpaid and undervalued by society. The explanation for this can be found in economics – or more precisely, the law of supply and demand.

The harsh reality is that lower paid “essential” jobs require few educational credentials. Moreover, the skills necessary to be, say, a cleaner, are easy to pick up as they are non-technical. This means that the pool of eligible workers is large, making it easy for employers to hire and fire.

Around the world, many essential workers just get by, living from pay-to-pay. Yet, during the pandemic, these “low wage workers,” according to Health Policy Watch, continued “to risk exposure to the deadly virus while celebrities and CEOs retreat(ed) to private mansions and islands for self-isolation”. This brought the gap between “have” and have nots” into stark relief.

In an opinion piece in The New York Times on 24 April 2020, Gene Sperling, a former economic adviser to Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama asked: “Will our overdue recognition of the contributions of so many workers lead to only temporary applause and pats on the back, or will it move us toward a true social compact ensuring economic dignity for all?”

Drawing inspiration from legendary human rights activist, Dr Martin Luther King, Mr Sperling wrote:

Fifty-two years ago, when the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. famously asserted the dignity of all work, he seemed to foresee this moment when it would become so clear that the labor of everyone – farmworkers, grocers, delivery drivers, caregivers, nursing assistants – was essential to all of our health and well-being.

“One day,” Dr. King told sanitation workers on strike in Memphis in 1968, “our society will come to respect the sanitation worker if it is to survive, for the person who picks up our garbage, in the final analysis, is as significant as the physician, for if he doesn’t do his job, diseases are rampant”.

In the words of Dr King: “All labor has dignity”.

Regards

Paul J. Thomas

Chief Executive Officer

Ductus Consulting