A SMALL PROBLEM WITH BIG NUMBERS

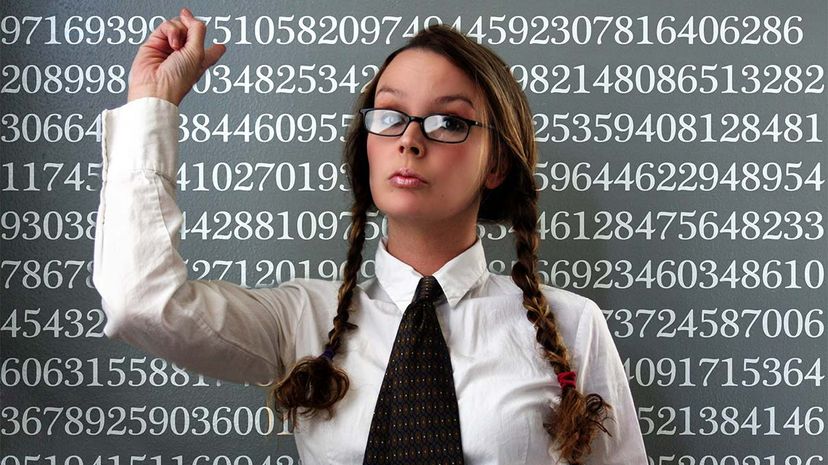

Our ancient ancestors had no need to understand excessively large numbers as their everyday dealings were with single-digits, such as two fish or three spears. Unlike us, they did not live in a world comprised of millions of streets, billions of people, and trillions in debt. And they certainly never encountered a Rubik’s cube with 43 quintillion possible configurations (that’s 18 zeros)!

In contrast, today’s news broadcasts often report absurdly huge numbers as businesses, scientists, and governments increasingly think in terms of millions (of dollars), billions (of stars), and trillions (in bailouts). These mathematical names are tossed around with casual disregard, thereby sealing their place in common parlance. Still, many of us do not have a visceral grasp of their size.

Understanding giant numbers is far from second nature – they perplex the human mind which is yet to latch on to the modern world’s explosion of massive numbers. As noted by one leading anthropologist, as a species we have evolved capacities that “… are naturally good at discriminating small quantities and naturally poor at discriminating large quantities”.

While getting a solid handle on incredibly big numbers isn’t easy, it’s not a problem for Google founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who both grew up fascinated with mathematics. So, when they registered the name of their new Internet search company in 1997, they chose the mathematical term, googol. Googol is the label for 10 raised to the hundredth power (10100) or 1 followed by 100 zeros.

Our young tech entrepreneurs thought that googol was an appropriate name for their search engine as it was going to index an unfathomable number of Internet web pages. However, due to a typographical error, the name was incorrectly typed as Google; the name stuck and Google Inc. was born.

Big numbers befuddle us – and not because we misspell them. Numbers as large as a googol are hard to comprehend and referring to them by name doesn’t help. There is not a googol of anything in the universe as the number is so mind-bogglingly mammoth it has no practical application.

Of course, smaller numbers used to quantify commonplace things – such as 2 dogs, 25 people, and 1,000 cars – are easy to comprehend. But when we encounter larger numbers, like a quadrillion, it becomes increasingly difficult to conceptualise them. Such numbers are so abstract, our eyes glaze over.

Consider a trillion – it effortlessly rolls off the tongue. Yet, when we express it in exponential format (1012) or its full format (1,000,000,000,000), we start to get a sense of how gargantuan it is. One trillion is a thousand billion, or comparably a million million. Whichever way you look at it, there are too many noughts to make sense of, so let’s put this number into perspective.

If you had spent $1 million a day since the birth of Jesus Christ, you still wouldn’t have chalked up $1 trillion in purchases. If you travelled back in time by a trillion seconds, you would end up circa 30,000 BC. And if you were to spend $1 million an hour, non-stop for 24 hours a day, it would take you 114 years to burn through $1 trillion.

In August, 2018 Apple became the first company in the world to crossover in to the four-comma club when its market capitalisation surpassed $1 trillion. Two years later, Apple’s market value doubled, making it the first publicly traded US company to pass the $2 trillion threshold.

World Bank data reveals that only seven countries have annual GDP figures greater than Apple’s $2 trillion value. With this amount to spend, you could buy Australia and New Zealand and still have a pocket full of change. You could also end world hunger many times over according to the United Nations.

Investopedia calculated that to equal Apple’s $2 trillion market cap, you would have to combine the net worth of the world’s top 24 billionaires. This provides a nice segue to our next humongous number – a billion. Using scientific notation, this number is expressed as 109 – the superscript tells you how many zeros there are after the one.

After discussing a trillion, a billion might sound small – but it’s not. Each billion is equivalent to a thousand million. Could you live on a billion dollars for the rest of your life? Well, spare a thought for the world’s richest individuals who each face the challenge of surviving on personal fortunes of over $100 billion.

In March each year, the American business magazine, Forbes, publishes a list of the wealthiest billionaires in the world. The 2021 Forbes list shows that Amazon founder, Jeff Bezos, is the world’s richest person, with a net worth of $177 billion.

Entrepreneur, Elon Musk, rocketed into number two spot with a $151 billion fortune*. French luxury goods tycoon, Bernard Arnault, took third place with $150 billion under his Louis Vuitton belt. And rounding out the top four in the centibillionaire club is Microsoft co-founder, Bill Gates, whose riches swelled to $124 billion.

The number of billionaires on Forbes 35th annual list exploded to an unprecedented 2,755 people who are collectively worth $13.1 trillion, up from $8 trillion on the 2020 list. Just to provide some perspective to this staggering wealth, Oxfam International reported that prior to the pandemic the (then) 2,153 billionaires in the world had more wealth than the 4.6 billion people who made up 60 per cent of the planet’s population.

If we drop down one notch on our scale of large numbers, we arrive at a more digestible number – a million – which has a power-of-10 notation of 106, where 10 is the base and the 6 is the exponent. A million is a thousand thousand, and while it’s the smallest of the big boys, a million remains the classic benchmark for other massive numbers.

As a million sits at the bottom of the “illions” ladder, it’s easy to view this as a paltry amount, but is that really the case? When was the last time you encountered a million in your daily life? Do you own a million of anything? Have you ever driven a million miles? Do you work in an office with a million employees?

When I was a boy, a millionaire was a very wealthy person whereas today that is considered to be a modest level of wealth. Nevertheless, a million is still a large number and anyone reading this post would be thrilled to strike it rich with a seven-figure windfall. Also, die-hard social media users work overtime trying to rack up a million plus followers.

Humans are visual creatures, so a common strategy for comprehending big numbers is to devise visual representations which provide a sense of scale. You can put a million into perspective by saying that one million acres is the size of 16 million tennis courts. Or that planting one million trees would cover an area of more than 15,000 football fields.

The trick to thinking about large numbers is to relate them to something that is meaningful – even something as simple as seconds. A million seconds takes almost 12 days to elapse, a billion seconds is about 32 years and a trillion seconds equates to around 32,000 years. In a similar vein, you could say that counting to a million would take days, counting to a billion would take years, and counting to a trillion would be impossible in one lifetime.

Telling a child that you could line up 109 Earths across the face of the Sun is far more comprehendible than clinically blurting out that the Sun’s diameter is 1.392 million kms. Equally, reporting that a destructive bushfire has rapidly burned an area equivalent to the size of a football field every second is easier to visualize than saying that millions of acres were destroyed.

■ ■ ■

Mathematics is the universal language of humanity and it connects all of us. Around the world and across civilisations, anyone with an elementary education can understand tens, hundreds, and thousands, but many of us struggle to quantify millions, billions, and trillions. So, instead of hurling brain bending numbers at each other, we should break them down so that they make sense for our own experience.

What’s next – getting our minds around a quadrillion (1015)?

*During 2021, Elon Musk passed Jeff Bezos as the richest individual on Earth. According to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, Musk had a net worth of $220 billion as at 30 January 2022.

Regards

Paul J. Thomas

Chief Executive Officer

Ductus Consulting