COUNTRIES FLEX THEIR MUSCLES

The postponed 2020 Olympic Games – which are now scheduled to kick off in Tokyo in July – will provide an international stage for countries to showcase their elite athletes. Spectators the world over will cheer for their nation’s sportsmen and women as they vie for Olympic gold. The fierce but friendly competition will fuel national pride and expose a positive side of nationalism – the celebration of the sporting success of those representing one’s homeland.

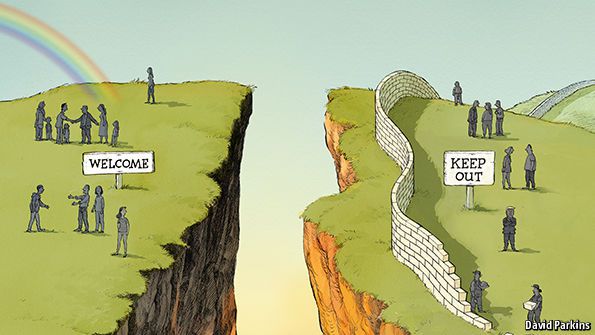

Beyond the Olympic arena, however, chest-thumping nationalistic patriotism has a dark side. It’s understandable that every country tries to instil a national consciousness among its own citizens. But when that patriotism morphs into a sense of superiority over other countries, it leads to a combative us-against-them mindset which is a poisonous ideology. In many parts of the world, patriotism has turned toxic.

Populist politicians have been selling nationalism as patriotism by promoting blind loyalty to one’s country to the detriment of global connectivity. Claiming to speak for “the people”, populists like Donald Trump have appealed to the anger and discontent of voters, tapping into their fears about jobs, race and immigration. In the West, many people feel left behind by technological change, growing inequality and the global economy.

Events over recent years show that there has been a nationalist backlash to globalisation. The UK’s decision to leave the European Union, Donald Trump’s win in the 2016 US presidential election and the growing momentum of right-wing parties in France, Austria and Germany all attest to this. In an increasing number of countries, the radical right – a group of extremist parties united by their hatred of immigrants – has surged in popularity.

These populist parties and their followers have been variously described as racist, xenophobic, anti-Islamic and anti-refugee. Parties of the far-right focus on tradition – real or imagined – and play on a nostalgia which yearns for simpler times. They want to turn back the clock to when national cultures were not influenced by immigration (and globalisation) and jobs were the preserve of native-born citizens.

This delusional hankering for the “good old days” was epitomised in Donald Trump’s right-wing rallying cry to “Make America Great Again”. Trump mistakenly believed that this greatness would be achieved by closing borders, curtailing trade and building a wall to keep out Mexicans. We should not forget that it was this kind of old-fashioned nationalism which helped fuel two world wars.

Following their defeat in World War I, the Germans felt humiliated and this enabled Hitler to exploit people’s feelings of resentment towards the ruling elite. Hitler also promised to make Germany great again. The parallels between how Trump and Hitler came to power are instructive. The rhetoric of both men was dangerously populists in nature. Not surprisingly, historians have been comparing Trumpism to fascism. One writer recently opined that:

It hardly takes a genius to see the similarities. Hitler promised to return Germany to her former glory by weeding out the traitorous politicians who had cost her the war. Trump promised to “Make America Great Again” by “draining the swamp”. Hitler blamed Germany’s problems on the Jews. Trump blamed Mexican “rapists and criminals”. Hitler’s supporters chanted slogans like “Im Felde Unbesiegt” (Undefeated on the Battlefield), Trump’s supporters had theirs too: “Build the wall”, “Lock Her Up”, and of course, his latest: “Stop the steal”.

As part of rebuilding the world after World War II, the Liberal International Order was created. Liberalism is an international (as distinct from national) worldview that opposes isolation and protectionism. The liberal vision looks for collective solutions to global problems by working co-operatively with the help of international institutions and alliances to make the world a better place. Nationalists, in contrast, want a more homogenous society and tighter controls by governments over territories and borders.

The mantra of nationalist politicians – “country first” – fuel calls to build fences and erect trade barriers. Yet since 1950, the burgeoning growth in international trade has helped make the world a more peaceful place. Free trade raises the cost of war by making nations more economically interdependent. The more people rely on trade with others, the greater the cost to all parties of a conflict.

One of the hallmarks of liberal internationalism is rule-based relations which are enshrined in institutions such as the United Nations. Under nationalism, however, we would see a more contested and fragmented system of economic blocs and regional rivalries. The desire to increase sovereign control invariably results in isolationist policies, particularly with regard to immigration.

In his final address to the UN General Assembly on 20 September, 2016 Barack Obama delivered a stinging rebuke to those who would build walls saying: “A nation ringed by walls would only imprison itself”. In the same speech, he defended liberal globalisation arguing that open markets, capitalism and democracy should remain the guiding forces of the international order.

… I believe that at this moment we all face a choice. We can choose to press forward with a better model of cooperation and integration. Or we can retreat into a world sharply divided, and ultimately in conflict, along age-old lines of nation and tribe and race and religion. I want to suggest to you today that we must go forward, and not backward. I believe that as imperfect as they are, the principles of open markets and accountable governance, of democracy and human rights and international law that we have forged remain the firmest foundation for human progress in this century.

It is paradoxical that the growing calls for a less open world would actually hurt the poor most of all. Since the end of World War II, free trade has lifted millions out of extreme poverty. It is irrefutable that globalisation has been good for the global poor. This point was also made by President Obama.

The integration of our global economy has made life better for billions of men, women and children. Over the last 25 years, the number of people living in extreme poverty has been cut from nearly 40 per cent of humanity to under 10 per cent. That’s unprecedented. And it’s not an abstraction. It means children have enough to eat; mothers don’t die in childbirth.

President Obama went on to say that “our international order has been so successful that we take it as a given that great powers no longer fight world wars; that the end of the Cold War lifted the shadow of nuclear Armageddon; that the battlefields of Europe have been replaced by peaceful union”.

Populist politicians are undermining liberal internationalism and this poses a threat to peace and prosperity. Less international co-operation will lead to increased distrust between nation-states and may even give rise to conflict. Nativism and its beggar-thy-neighbour policies is a backward and dangerous step for the world. In the words of the old adage, it really is a case of “united we stand, divided we fall”.

The rise of the new radical right reflects a deep social and economic malaise affecting an increasing number of nations. The past decades have ushered in an unprecedented level of socio-economic change and voters are expressing their dissatisfaction at the ballot box. Only time will tell how long this anger and resentment lasts. What is clear is that the rhetoric of the far-right has struck a chord with a critical mass of voters.

The world’s political landscape has been transformed by a nationalist movement which has gone global.

Regards

Paul J. Thomas

Chief Executive Officer

Ductus Consulting

Hello Paul,

As someone interested in international politics/economics, I really appreciate your explanation/clarification of Liberalism versus Nationalism.

The recent local and pointer by-election in the UK certainly proves your point regarding populism.

Thank you!

Des