THE LINES HAVE SHIFTED

We all understand the difference between up and down. We also know the distinction between north and south. But when it comes to left and right in a political sense, many of us are less clear. What does it really mean to be left-wing? How does this vary from those who lean to the right?

The terms “left-wing” and “right-wing” define opposite ends of the political spectrum, yet there is no firm consensus about their meaning. Over time, these labels have become blurred. Tony Blair once argued that the contrast between the two had melted away into meaninglessness.

The genesis of the political categories “left” and “right” date back to eighteenth century France and the French Revolution. Members of the National Assembly were seated according to their political orientation. Supporters of the king sat to the right of the Assembly president with supporters of the revolution to his left.

In line with this historic division, contemporary left-wingers are said to be anti-royalists who favour interventionist and regulated market economic policies. Right-wingers, on the other hand, are said to be monarchists who favour laissez-faire, free market economic policies.

While those on the left support higher taxes on the rich and welfare for the poor, the right favours lower taxes on businesses to help them grow. The left believes in an equal society and big government whereas the right argues that social inequality is unavoidable and that governments should play a limited role in people’s lives.

The Australian Labor Party has traditionally been seen as left-wing (socialist) with historic ties to the union movement. The Liberal Party of Australia has customarily been seen as right-wing (capitalist) with a long-standing pro-business posture. Many see this partisan profiling as outdated in describing Australia’s modern political landscape.

A case in point is the issue of Australia becoming a republic. Based on traditional ideology, you would expect this cause to be championed by the “anti-royalist” Labor Party. Yet the push for a republic has been spearheaded by a member of the “monarchist” Liberal Party.

Past prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, is a Liberal blue-blood. (NB: Left-wing parties are typically associated with red, the colour of revolution, while right-wing parties are often associated with conservative blue.) He is a former investment banker who – uncharacteristically for a conservative politician – is also a staunch supporter of the Australian Republican Movement. Turnbull co-founded the movement.

In trying to discard the monarchy (via a referendum in 1999), Turnbull was seen to have taken a left-wing stance which caused some right-wing hardliners to label him a turncoat. Still, he is not the only Australian politician to be off course in a strict ideological sense. Former Labor treasurer, Paul Keating, lurched to the right economically.

Keating’s laudable economic reforms included deregulating the financial system, floating the Australian dollar, reducing import tariffs and introducing compulsory superannuation – sound initiatives that a Labor treasurer was not expected to do. It’s said tongue-in-cheek that Keating was Australia’s best “Liberal” treasurer and the architect of neo-liberalism in Australia.

Many of Keating’s reforms were based on the 1981 Campbell Inquiry Report into Australia’s financial system. John Howard instigated the inquiry when he was Liberal treasurer under prime minister, Malcolm Fraser. But Howard disappointed his traditional business supporters by implementing only one of Campbell’s 260 recommendations.

Ironically, it was Keating who introduced many of Campbell’s recommendations. He implemented a globalisation agenda which made Australia internationally competitive and opened our economy to the rest of the world. Unsurprisingly, big business embraced Keating – even though the Labor Party and corporate Australia are supposed to be adversaries.

So, how left-wing was Keating as a left-wing politician? In reality, he moved the Labor Party to the right of centre. So, the message is clear: While some may argue that ideological creeds are reflected in the policies of each party, this is often not the case.

If the truth be told, political viewpoints along the left-right scale do not fit neatly into one ideological camp. Within each camp, there are factional groups who believe that some things outweigh others. So, an individual may identify with left-wing ideals on one issue but consider themselves right-wing for everything else.

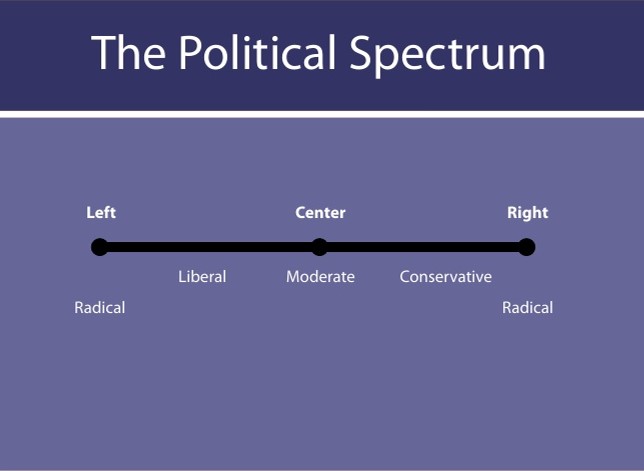

Those whose political outlook sits somewhere in the middle of the left-right divide are classified as taking a “centrist” stance. And to complicate things further, those who hold extreme political views belong to either the far-left or the far-right.

People on these outermost poles of the political spectrum often see themselves as aggrieved individuals. They are radicals who are deeply estranged from mainstream political mores. Their degree of alienation from contemporary society can be seen in their extreme ideologies.

Both the far-left and the far-right have a victim-like mentality and employ militant strategies. Their political engagement relies upon force, violation of civil liberties and disdain for democratic ideals and practices. They normalise violence in their attacks on governments, globalisation and social elites.

The far-left includes Islamic terrorists while the far-right boasts white supremacists and neo-Nazis among its ranks. These extremist hate groups engage in violent acts and display many parallels. As they have overlapping tactics and stances, some academics contend that it is misleading to classify the far-left and far-right as opposite poles.

It is suggested that a more realistic classification is provided by the Horseshoe theory. This theory asserts that the political spectrum is not a straight line with opposing ends. Rather, it is a horseshoe with its farthest outliers bending in toward each other and sharing a number of similar beliefs.

To illustrate, supporters of the extreme right and extreme left are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories even when they are contradicted by mainstream science or factual evidence. These theories include the belief that coronavirus vaccines are harmful, climate change is a hoax and the US government planned the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

One area where the far-left and far-right markedly differ is in their interpretation of the past. As noted in the US online newsletter, The Perspective, these interpretations dictate their political stances and calls to action.

The far-right expresses nostalgia for the past and actively works to preserve their history, regardless of what that might mean in today’s context. … Conversely, the far-left … associates the past with its ills – slavery, sexism, and other injustices. History and its institutions are not to be preserved and cherished, but rather, an embarking point from which to begin reform.

History is in the eye of the beholder and so too is populism. There is no agreed definition of populism – it means different things to different people. In political science, populism is seen as an approach that frames politics as a battle between two opposing groups. In his book, Populism: A Very Short Introduction, Cas Mudde labels these antagonistic groups as the “pure people” (ordinary masses) and the “corrupt elite”.

Populism is not sustained by a single political ideology. Rather, it describes a style and approach to politics. Populism can be deployed in the service of almost any ideology – left or right, moderate or extreme. Populists can come from all parts of the political spectrum and they have popped up all over the world.

Think Marine Le Pen in France, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and, of course, Donald Trump in the US. All of these populist leaders climbed to prominence by dividing people into good or bad. Populism defines our current political age. In the words of one US journalist:

Once in power, populist leaders represent “a threat to liberal democracy” … (such as) Trump calling the press the “enemy of the people,” criticizing judges, resisting congressional oversight, claiming that elections are “rigged,” flouting laws, and claiming that a “deep state” of bureaucratic actors is out to get him to deny the will of the people he represents. It happens with other populist leaders all over the world.

■ ■ ■

It’s axiomatic that thinking in terms of a left-right spectrum is outdated. While these binary labels may be convenient shorthand descriptors, they are too generic. People hold a range of opinions on social and economic issues and these do not fit neatly in the traditional left-right continuum.

Also, citizens care about the matters that affect them and not the political ideology that supposedly underpins a given issue. Further, humans can hold seemingly contradictory beliefs. All of this makes the political spectrum largely meaningless, but we continue to use it due to laziness. As noted in the online magazine Quillette:

Putting people into one of two ideological boxes is far easier than understanding their unique point of view. Reducing politics to a simple contest between right and left is far easier than reasoning through hundreds of issues. Humans generally prefer simplicity to truth and would rather sign up for a “side” than do the hard work of thinking.

Whether you swing left, lean right or aim dead centre, it’s incumbent on all of us to stay politically informed.

Regards

Paul J. Thomas

Chief Executive Officer

Ductus Consulting

A thought provoking blog! There is nothing simple about politics, the people or the parties. It is a question of analysing, understanding, and thinking, the how and the why overarched by values and beliefs that make politics anything but simple.

It is important that we stay politically aware. However, many of us are egocentric and apathetic when it comes to politics. Part of changing attitudes may come from school education. Political studies need to be given greater status in our school curriculum. The most effective way to learn is by doing, so let’s add some democracy to schools. Elections of pupils to school bodies, referendums on school rules and political debates etc.

Paul, you have captured the essence of politics – overly complex and missing what should be important – doing the basics right and representing what the nation actually needs.

Hello Paul,

Interesting to read the history, explanation and limitations of a political model that we all take for granted. My learnings from your research are that a non-dualistic approach, improved articulation and staying informed can overcome the disadvantages of referring to an out of date concept. Thank you,

Des