NEVER SAY DIE

The human species has a natural shelf life due to aging – a debilitating condition that no one can escape. Our biological functions decay over time and the Grim Reaper eventually catches up with all of us. Despite the amazing advances in medicine and the resultant rise in life expectancy, you can’t keep Father Time at bay forever. Still, there are those who believe that humans can significantly extend their expiry date.

It is generally accepted that the apparent limit to human lifespan is about 120 years. The life extending treatments necessary to ward off the ailments that accompany old age and stop people living well beyond 120 years do not currently exist. So, at this stage, we are all doomed to age and die – assuming that some other fatal event does not take us out first.

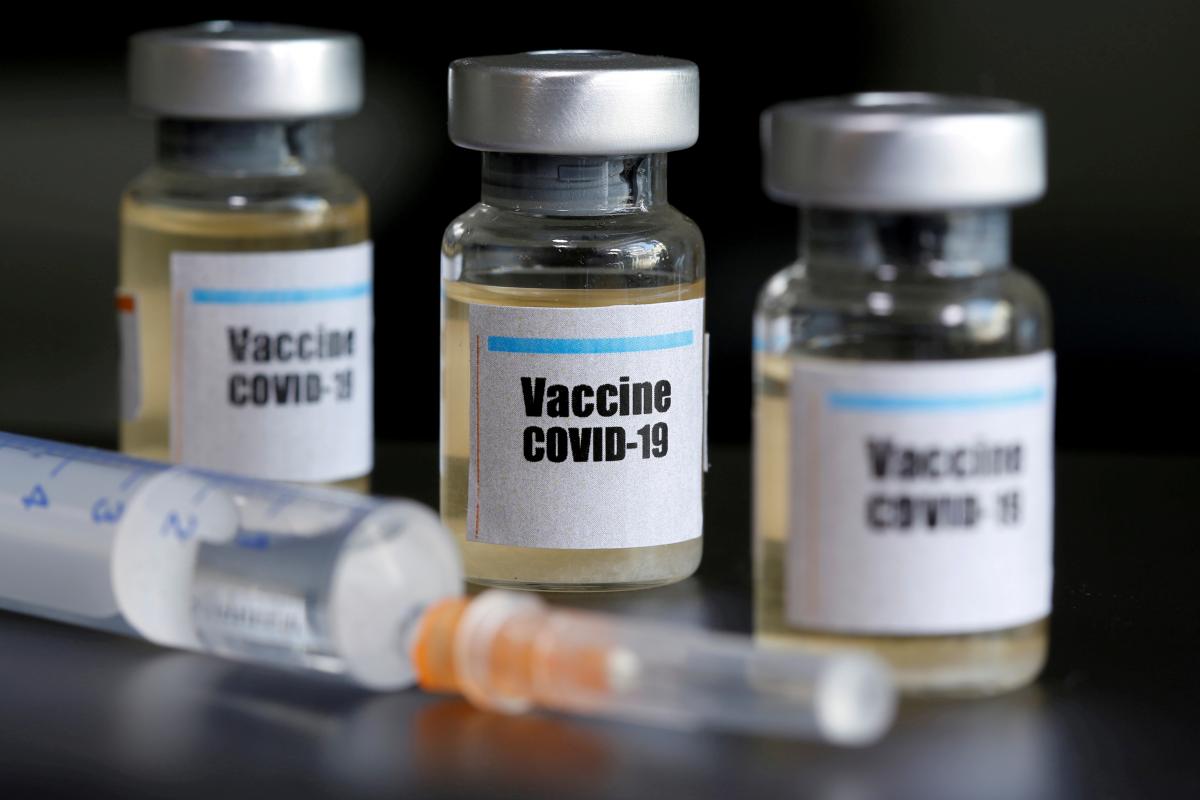

That said, the good news for those who want to stay young and live longer is that scientists are working to recalibrate the human body clock. It’s already evident that people over 50 aren’t aging as fast or poorly as their parents, and anti-aging research is set to improve this trend. Over time, medical treatments to head off the slow march towards death will become increasingly common.

We know that the duration of human life is influenced by genetics, the environment and lifestyle. Yet the causes of aging are extremely complex and unclear. With the rise in longevity clinical trials, more answers – and questions – are emerging. Scientists are now asking whether our natural genetic makeup is limited to a maximum span of 120 years or whether this boundary can be breached.

The study of longevity is a developing science. Our genes harbor many secrets to a long and healthy life and researchers are trying to find the key within our genome to edit out bad stuff. Genes are akin to little packets of information found in each cell in our body. These packets contain critical instructions which tell our body how to grow and develop.

An online article by Nature Publishing Group explains that:

The action of a single gene can have huge effects on how long a creature lives. This may seem hard to believe because so many things go into determining lifespan, including a host of lifestyle factors and a long list of diseases. Nonetheless, remarkable effects on lifespan are seen when particular genes are deleted from an animal’s genetic sequence. Furthermore, research – particularly that involving microscopic roundworms – continues to provide scientists with tantalizing clues about the molecular pathways involved in aging.

Researchers at the University of Rochester have discovered that one of the keys to longevity resides in a gene called Sirtuin 6 or SIRT6. The Sirtuin family of genes and their proteins play a role in controlling aging by repairing damaged DNA, thereby preserving health and youthfulness. SIRT6 has also been identified as a critical regulator of telomere integrity.

Telomeres are an essential part of human cells that affect how our cells age. Telomeres are caps at the end of each strand of DNA which protect our chromosomes, just like the plastic coating (tips) on the ends of shoelaces. Without tips, shoelaces would become frayed and no longer able to do their job. In the same way, without telomeres, DNA strands become damaged resulting in the inability of cells to fully replicate.

The cells in your body are continually dividing and renewing. With each round of cell division, telomeres become shorter. Eventually, our telomeres become so short that the genes they protect could be damaged, so the cells stop dividing and self-destruct. This programmed cell death (called apoptosis) contributes to aging.

Apoptosis is “cell suicide” and scientists believe that reducing the rate of telomere shortening could slow the body’s cellular clock. Research shows that longer telomeres are associated with a longer lifespan while shorter telomeres are connected with the ailments of aging: heart disease, cancer and osteoporosis. If scientists can preserve or elongate telomeres, humanity will be one step closer to a genetic Fountain of Youth.

While most scientists are purely trying to extend life, some researchers are brazenly focussed on helping people dodge death altogether, by turning science fiction into science fact. To many, the quest for immortality seems nonsensical. Even so, Ray Kurzweil, Google’s Director of Engineering, preaches that “immortality is within our grasp”.

Google co-founder, Larry Page, has invested $1.5 billion of Google’s money into a R&D project called Calico, which aims to “cure death”. Calico is short for the California Life Company and the mission of this Google-backed biotech firm is to “harness advanced technologies to increase our understanding of the biology that controls lifespan”. For the masters of the universe at Google, death is the ultimate engineering problem to be solved. The company believes that it will eventually be successful at hacking the code of life.

Aging and death are existential certainties, which is why many consider Google’s anti-death project to be unbridled hubris. While the search for immortality is an epic goal, few believe that Google will solve “the problem” of death. A more likely outcome is that Calico will find ways to dramatically extend human life. That, in itself, raises a series of socio-economic questions regarding overpopulation, class divisions and the affordability of anti-aging technologies.

What seems forgotten by Calico’s backers in their conquest of death is that mortality has value, which is why immortality is not an easy sell. Research reveals that most people don’t like the idea of living forever. As outlined in a 2017 Smithsonian Magazine article:

… a large percentage of today’s population also subscribes to religious beliefs in which the afterlife is something to be welcomed. When the Pew Research Center asked Americans in 2013 whether they would use technologies that allowed them to live to 120 or beyond, 56 percent said no. Two-thirds of respondents believed that radically longer lifespans would strain natural resources, and that these treatments would only ever be available to the wealthy.

Google has resourced its science start-up with some serious intellectual firepower and these scientists and researchers are working behind-the-scenes to challenge the inevitability of death. The proponents of a “transhumanist” movement called the Church of Perpetual Life support Google’s initiative. They believe that technology could one day see our consciousness digitised into computers, turning us from biological humans into robots – the so-called singularity. (Some fear that this will see artificial intelligence morph into a modern-day Frankenstein’s monster!)

For Silicon Valley’s death-cheating initiative to be successful, it must find a way to defy the laws of thermodynamics so that an individual can live forever. The key to immortality is tied to the second law of thermodynamics which states that everything must decay. The cells in our bodies follow that rule and eventually deteriorate. That leads to entropy – the inescapable and irreversible process of disorder and eventual death.

Turnover is a basic characteristic of life. Ergo, the search for the elixir of everlasting life runs against the natural order of things as all living organisms ultimately die. Humans are not biologically immortal and no amount of R&D money can alter that fact. We will all eventually kick the bucket as immortality – the Holy Grail of biological sciences – is a fairy tale. Even if it were possible, I think that a never-ending life would be a fate worse than death.

The death of death has been grossly exaggerated.

Regards

Paul J. Thomas

Chief Executive Officer

Ductus Consulting